The fall of Avdiivka to Russian forces after another mammoth siege is a sobering reality for all the belligerents of the Ukraine war, which now enters its third year. The coming year will be tough for everyone – tough for Russia, even tougher for Ukraine – though neither are likely to fold in 2024. It will be increasingly tough, too, for Ukraine’s western backers in Europe and America. In an extended version of the essay extracted in the Sunday Times on 25 February, Michael Clarke explains.

The second anniversary of the Ukraine war was remarkable for the unanimity among the most important Western leaders about what it represented and hence the need to see this war in a longer time-frame. It was presented as a struggle, not just for the future of Ukraine as a free country, fighting off the naked aggression of Russia – a ‘neo-imperialist state’ as the British Foreign Secretary characterised it. The war was also widely interpreted as a struggle over the future direction of global politics more broadly. According to their multiple statements, the war in Ukraine has become the line in the sand Western leaders have finally drawn against the march of dictatorship, autocracy and outright gangsterism that has swept ever further forward during the last decade, not just in Europe, but also in Africa, the Middle East and many parts of Asia. Western leaders all found their own rhetoric to describe what they were facing, but they all had a similar message; that it would be a longer struggle than most people anticipated in 2022 and that the outcome would matter greatly to everyone, not just to Kyiv.

What they didn’t want to say too loudly was that all this marks the return of industrial-age warfare to Europe. It also marks the end, at least for a while, of more than thirty years in which the continent has enjoyed a ‘peace dividend’ of low defence spending against increasing social spending. In 1990 Britain, for example, was spending about the same on defence as on health. By 2022 it was spending less than a quarter on defence as on health. That, in microcosm, was the thirty-year peace dividend. All very welcome and appropriate; but now it’s over, at least for as long as Putin’s Russia cleaves to its present imperialist ambitions.

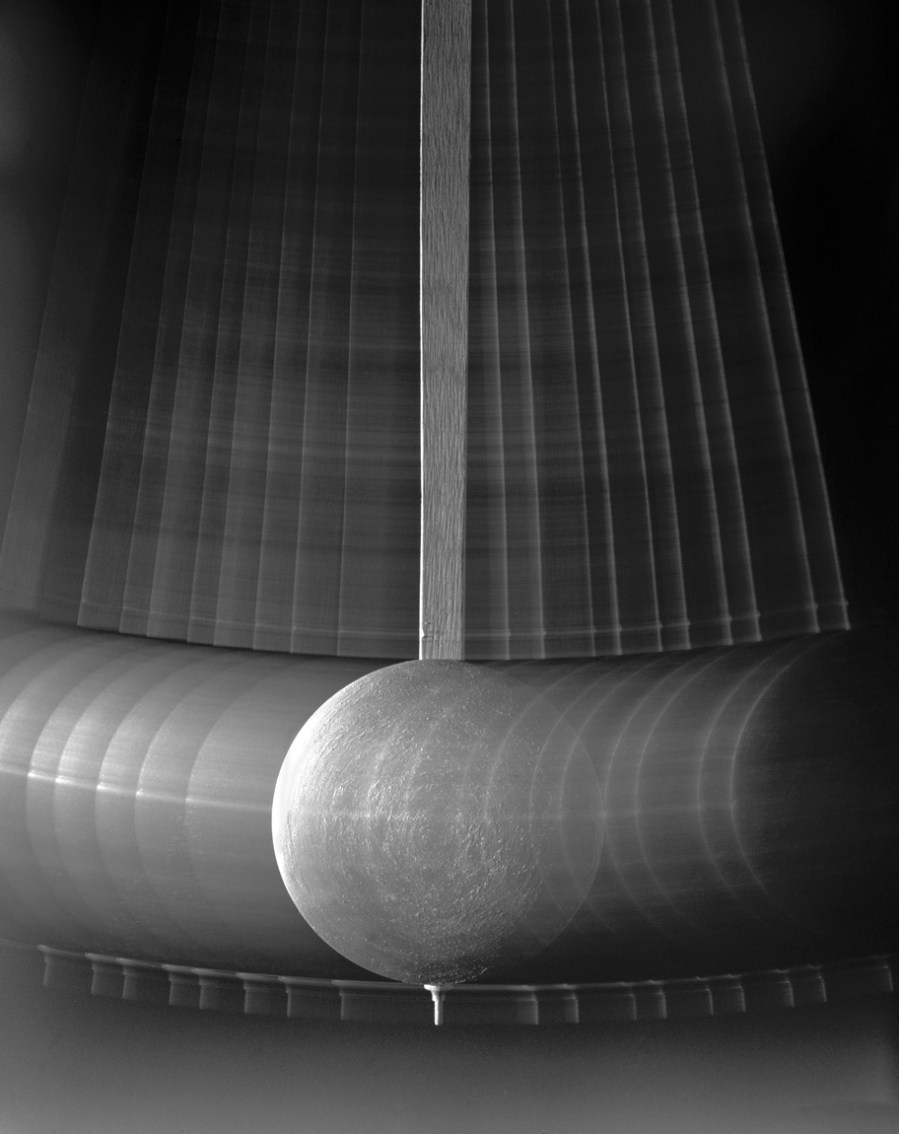

Generations of European leaders barely thought that within their lifetimes Europe would again be plunged into this sort of industrial-age warfare. But we’ve now had two years of it. The winners of industrial-age warfare are those who can produce and deploy enough war materiel to overwhelm their opponents over long military campaigns. Industrial-age wars are noted for the way the military pendulum swings back and forth, ultimately according to the way the pendulum of war production swings.

This is not the challenge NATO expected. For years, the alliance prepared for a ‘come as you are war’ – win or lose through what you start with. It was expected to be a short but decisive conflict under the nuclear shadow. But the fundamental nature of the Ukraine war is closer to the Second World War than anyone could have imagined. NATO leaders are having to re-think what sort of wars they are trying to deter as they face the next twelve months, just as Ukrainian leaders are preoccupied with how to stay in this one.

That’s the way industrial-age wars tend to go. In 1941 the struggle in Europe tipped geopolitically and irrevocably toward the Allies. Hitler over-extended his forces invading the Soviet Union in June; and the United States joined the Allied powers in December when Japan attacked it at Pearl Harbor. But that decisive swing of the geopolitical pendulum wasn’t felt for almost a year. And 1942 was a terrible time for the Allies – fraught, dangerous and depressing. It was not until the Second Battle of Alamein in October 1942 that the tide seemed to turn. As Churchill put it, ‘Before Alamein we never had a victory; after Alamein we never had a defeat’ – not technically accurate, but true enough.

It could turn out this way for Ukraine and the West. From a resource and geopolitical perspective, the West is decisively stronger. Even excluding the US and Canada, the European powers alone are twelve times richer than Russia, with a population three times greater and with peacetime armed forces half as big again as Russia’s. And within NATO the West has five times more aircraft, three times more ships, and three times the armed forces personnel. Only in ground force equipment is Russia more evenly matched with NATO. Geographically, the West has far better air and sea access to all the areas that matter. The inclusion of Finland and Sweden in NATO, for example, makes the Baltic a NATO lake. Most significant for Ukrainian leaders, the western powers have all, from the beginning and repeatedly since, pledged to support them in this war ‘for as long as it takes’.

But it doesn’t feel much like that in Kyiv at the moment. Its forces have finally withdrawn from Avdiivka, because they ran out of ammunition. Its cities are suffering from nightly Russian air attacks because they are short of air defence missiles. Ukrainian casualties are mounting as recruitment numbers fall, and Kyiv watches in dismay as a dysfunctional Washington argues over whether it will be pulling the rug from under it altogether in the coming months. Doubtless, Kyiv hopes this year will prove to be its 1942 and end with the geopolitical pendulum decisively in its favour. But it must battle on four different fronts if it is to make this year seem like the dark before the dawn.

One front is the ground war. With Ukrainian troop numbers and war stocks running low – rationed in all sectors – and Russian forces prepared to take huge losses in both, Kyiv seems reconciled to losing some of its territory along the fighting front this year. Avdiivka is a genuine loss for Kyiv. It’s also a loss for Oleksandr Syrskyi, Ukraine’s new Commander-in-Chief. He tried to save Avdiivka by sending Special Forces and the 3rd Assault Brigade to keep the lifelines open for the troops holding on in the town. But they failed to relieve the siege. The 3rd Assault Brigade did rather less well than had been expected, which showed up some basic and persistent problems of command and experience within Ukraine’s ground force formations. And when the withdrawal was eventually ordered on 16 February, it was not well coordinated. Up to 1,500 of the 3,000 Ukrainian troops involved appear to have been either killed or captured. Numbers are still hard to establish with certainty. Avdiivka certainly involved heavy losses for Ukraine and has not helped Syrskyi’s reputation as the first military campaign on his watch as C-in-C.

Further north, Kupiansk – gateway for the Russians westward into Kharkiv, or southward towards Slavyansk and Kramatorsk – might be next. Some 40,000 Russian troops appear to be pushing, yet again, around Kupiansk. The Ukrainians will try to dig in – yet again – further south and west, particularly around Slavyansk and Kramatorsk, to prevent Russian forces gaining the whole of the Donbas region, though they may not be able to prevent the Russians from taking some of Kharkiv back, after they retook the area in autumn 2022. Ukrainian forces would be confident that they can beat back Russia’s high troop numbers in these imminent offensives, even very high numbers, if they had enough ammunition. But the simple fact is that they don’t. Nevertheless, after taking Mariupol, Severodonetsk, Bakhmut and now Avdiivka, following months of heavy fighting for each, the Russians have shown no propensity to maintain any offensive momentum. They take their time to recover from these bloodbaths, and the Ukrainians will want to make the most of the pause.

A second front is the Black Sea, where Ukraine has shown real initiative in effectively chasing Russia’s Black Sea Fleet out of its base at Sevastopol with innovative attacks on enemy warships. So far, it has reduced the Black Sea Fleet by about 30 percent, sinking or disabling the flagship cruiser, a kilo-class submarine, a supply ship, a missile corvette, four of the fleet’s nine landing ships and an array of patrol boats and landing craft. Thanks to the 1936 Montreux Convention, no other Russian warships are allowed into the Black Sea, so Moscow cannot replace these losses from its Northern or Pacific fleets. It has effectively ceded control over the western Black Sea, allowing Kyiv trade access to the Danube Basin and the Mediterranean. Some 120-130 ships a month are now leaving Ukraine’s south-western ports, which is a return to the pre-war levels of early 2022. Most significantly, Ukraine’s success in making Russia’s position in Crimea insecure gives it a strategic lever against Moscow which – they know – enrages Putin. His seizure of Crimea in 2014 was his imperialist pride and joy.

A third front is the air war, where Russia, after a shaky start, has made its natural dominance count. This was seen particularly in its ability to blunt Ukraine’s summer offensive against the Russian ‘land bridge’ to Crimea. Apart from Iskandr ballistic missiles and Russia’s Kh-101 cruise missiles launched from heavy bombers, its low-flying Ka-52 attack helicopters and its improvised FAB-500 family of heavy glide bombs, launched by high-flying Su-34s and Su-35s up to 25 miles behind the lines, has proved deadly for Ukrainian ground forces. In the last twelve days of Russia’s Avdiivka offensive, its aircraft – operating well behind the front lines – launched about sixty big glide bombs each day against Ukrainian fixed defensive positions. Their influence on Ukraine’s ammunition-starved troops was decisive. Russian drones accounted for another 30-40% of Ukrainian casualties. And with Iranian drones and North Korean ballistic missiles bolstering its own diminished inventory, Moscow has been able to barrage both the front lines and Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure simultaneously. Kyiv is forced to choose where to site its scarce air defence weapons; protecting its soldiers or its civilian centres?

Ukrainian military chiefs will hope that the introduction of western F-16 combat aircraft during the year will make a difference. Ukrainian airpower somehow managed to shoot down a number of SU-34s/-35s during February, though it is not yet clear quite how. But even if a projected hundred F-16 aircraft are available before the end of the year, there are no guarantees they will turn the air war for Kyiv. The F-16 is certainly a good combat airframe, but its effectiveness depends on the weapons and systems that back it up, and that remains uncertain. So, too, the limited force of F-16s will undoubtedly be subject to attrition once it goes into combat.

Kyiv will aim to hold the Russians as best it can on these three fronts, to buy time to win on the fourth – and ultimately most decisive – front; the gearing up of its war industries for 2025.

Ukraine faces a Russia that has 470,000 troops in theatre. Moscow can probably rotate them in and out with another 400,000 recruits this year, even without more general mobilisation. It has 2,000 tanks in Ukraine and can probably produce another 1,500 a year to replace its extravagant tank losses – if not of its tank crews. It has got 7,000 armoured vehicles in Ukraine and can probably produce another 3,000 a year. Russia thinks it will need four million artillery shells this year and is expected to get two million of them from North Korea while it brings more out of its three million shells in dilapidated storage. On this basis, Russia can certainly sustain its attritional war for the coming year. But an influential report written by Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds of the Royal United Services Institute points out that, hidden within these figures, there are real structural weaknesses in Russia’s ability to sustain such numbers into 2025-26. It will depend on supplies and components from Iran, North Korea, Belarus and Syria. Russia’s war production, says the RUSI report, will effectively plateau in some of the most critical sectors from 2025. By then, Ukraine’s own ramped-up war production will begin to have greater effect.

This is where the West’s commitment to Ukraine and its changing expectations of European war become the make-or-break factor. Ukraine can only prevail in this struggle by drawing on the West’s ultimate production capacity. The western powers – immensely stronger and better equipped than Russia and its despotic allies – can swing the geopolitical pendulum decisively against Putin’s imperial adventure in Ukraine. They can sustain Ukraine this year and let the pressure build in the two years after that. They can confront Russia with the prospect of being beaten at its own attritional game, without wrecking their own economies in the process.

All the West has to do is deliver on its oft-repeated promises. For Ukraine and NATO, the coming year looks increasingly like 1942. The problem is that it isn’t yet clear which way the strategic pendulum will have swung by the end of it. In the last two weeks, Western leaders have certainly been talking the talk about supporting Ukraine ‘for as long as it takes’. But it still isn’t clear if they, or their publics, are yet ready to ‘walk the walk’ in that respect.

Michael Clarke is co-author of Tipping Point: Britain, Brexit and Security in the 2020s, London, I.B. Tauris, 2019 and Britain’s Persuaders: Soft Power in a Hard World, London, I.B. Taurus, 2021. He is the former Director General of the Royal United Services Institute and Visiting Professor of War Studies at King’s College London. Twitter: @MikeClarke2020s